A tiny gravesite on Tasmania's East Coast at Bicheno is home to the state's smallest state reserve, and subject of one of the state's oldest mysteries.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

$0/

(min cost $0)

or signup to continue reading

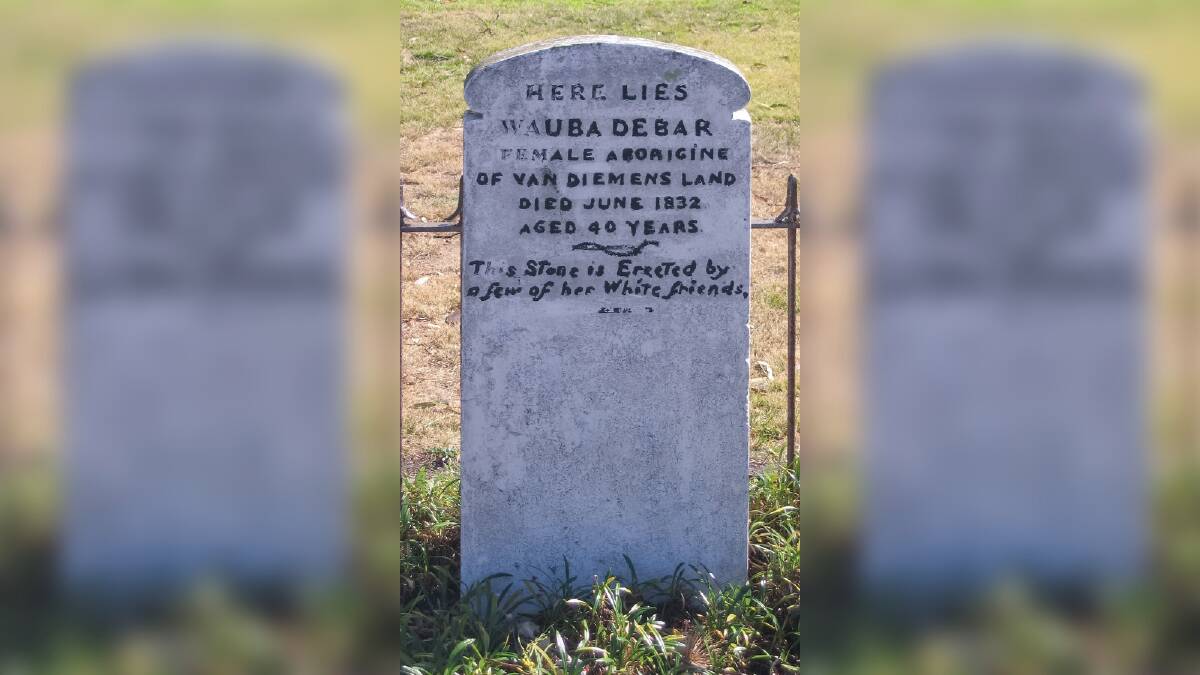

The grave reads: "Here lies Wauba Debar. Female Aborigine of Van Diemens Land. Died June 1832. Aged 40 years".

While there are many stories about who Wauba Debar was, the reality may well have never been told, and could even be buried deep beneath the ocean.

Stories about Wauba Debar's exploits range from having saved two sealers, one of them her husband, from drowning to simply being part of the paredareme tribe at Oyster Bay that subsisted by having a close relationship with the ocean.

Established research and long-told cultural stories have shown that female members of ocean reliant Tasmanian Aboriginal groups were the primary seafarers, often swimming to great depths to collect abalone from deep under seas rocks, or harvest periwinkles from rocky outcrops.

And while a handful of historians have dived into the facts around Wauba Debar's story, there is minimal concrete evidence of who she was and whether she actually existed as the legendary figure she has come to be known.

That legendary figure has her name inscribed on the headstone at Waubs Bay alongside the line, "this stone was erected by a few of her white friends". The grave site is surrounded by a small fence, and the fenced area is the entirety of Tasmania's smallest state park.

But the story that lies between Wauba Debar's body being first laid into the sandy Bicheno ground, and the commemoration of her memory through Shane Gould's Devil of a Swim at Bicheno every year is anything but dead.

University of Tasmania Pro Vice Chancellor of Aboriginal Leadership and Aboriginal history researcher Professor Greg Lehman said the truth was floating around somewhere, waiting to be found.

"People have touched on it, but nobody really has a definitive article on it," he said.

"All that we really know is an Aboriginal woman had been buried there.

At its heart it's a rich story of frontier conflict, with some depth of human relationships and regret, which are unusual in these sorts of interactions.

- Professor Greg Lehman

Even the pronunciation of Wauba Debar's name has changed and morphed over time.

Wauba is sometimes said war-bar, and Debar said as de-bar, but others have said the true name is more of an amalgamation of the two - Waubedebar said more like wor-badda-bar.

And while the life of Wauba Debar is the legend, it is the stories that have been told after her death that have made it so.

Research from the University of Technology Sydney's Megan Stronarch and Daryl Adair posited it was likely, despite her gravestone inscribed that she died in June 1832, Wauba Debar had actually died at least 10 years earlier, and that it had been during a voyage from Hobart to the Furneaux islands on a sealing trip.

After stopping at Bicheno, Debar was thought to have tried to escape from who were her likely captors, before she was recaptured and eventually died.

"Wauba Debar had, I suppose, been captured in like manner, and taken to be a slave and paramour, and possibly died of injuries sustained in the capture, which, no doubt, was not done very tenderly," explains a piece in The Examiner written by Edward Cotton, a settler on the East Coast, in 1893.

She, poor soul, was buried decently, perchance reverently, and I suppose other of the captured sisters would be present by the graveside on the shore of that silent nook near the beached boat.

- Edward Cotton, a settler on the East Coast, in 1893

Ms Stronarch and Professor Adair found a diary entry from Captain James Kelly which described a landing at "Waubs Boat Harbour" on January 24, 1816, and concluded this meant the grave had already been interred at that stage. It was thought the grave was initially marked with an inscribed slab of wood.

Professor Lehman said the first knowledge he had seen of the grave being marked was from 1820 in the report of an explorer called Henry Rice.

"He reported to Governor Sorrell that settlers had buried a woman called 'Campbell's black woman' at Stoney Boat Harbour, which is now the Gulch," he said.

"We do have a record that the grave did in fact belong to 'Campbell's black woman'."

Professor Lehman said Wauba Debar's name might, in fact, be a classic question of the chicken or the egg.

"The name Wauba Debar, I personally don't believe that's actually her name," he said.

"Legends tend to emerge out of things that get mixed up and conflated. I think it's much more than a coincidence that the woman's name and the place the grave is sounds the same.

Legends tend to emerge out of things that get mixed up and conflated. I think it's much more than a coincidence that the woman's name and the place the grave is sounds the same.

- Professor Greg Lehman

"I think the name was never really known and the grave just came to be known as the grave of Wauba Debar."

But in his research Professor Lehman had hypothesised where the body had come from, how it got there, and why it still carried such significance about 200 years later.

"I think it represents something ... I think it represents a very early form of recognition of how horrible colonial times could be," he said.

He believes the body of the woman that has come to be known as Wauba Debar was initially buried after the massacre of a group of local Aboriginal people by a landowner called John Allen and his troupe.

Allen's land, called Milton Farm, had been subject to multiple attacks from Aboriginal people. After the second such attack, Allen is thought to have invoked revenge.

Like Wauba's, Allen's story has become clouded.

Some records show Allen held out during a siege of his property against between 13 and 18 Aboriginal people with a rifle, while others concluded he headed out with a "hunting" troupe to exact revenge on the first Aboriginals he found.

Either way, Professor Lehman believes the act of taking the life of an Aboriginal person or people, played on Allen's mind to the point that at least 23 years after Wauba Debar's death, he paid to have a headstone placed at her grave in 1855.

No matter what you might say, these people were human beings at the end of the day, and I reckon this was [Allen's] way of acknowledging what had happened.

- Professor Greg Lehman

"It says something that goes to the heart of Tasmanian colonial times. It's kind of an acknowledgement that terrible things did happen."

But Wauba Debar's story does not finish there.

- The second part of this story will feature in the next Sunday Examiner

What do you think? Send us a letter to the editor: