- This is the second part in a story about legendary Tasmanian Aboriginal figure Wauba Debar. The first part is available online at examiner.com.au.

Before Ariarne Titmus was Shane Gould, and long before Shane Gould was Wauba Debar.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

or signup to continue reading

While Wauba Debar might not have been beamed around the world for her Olympics heroics, she had an impact on the East Coast community like no other.

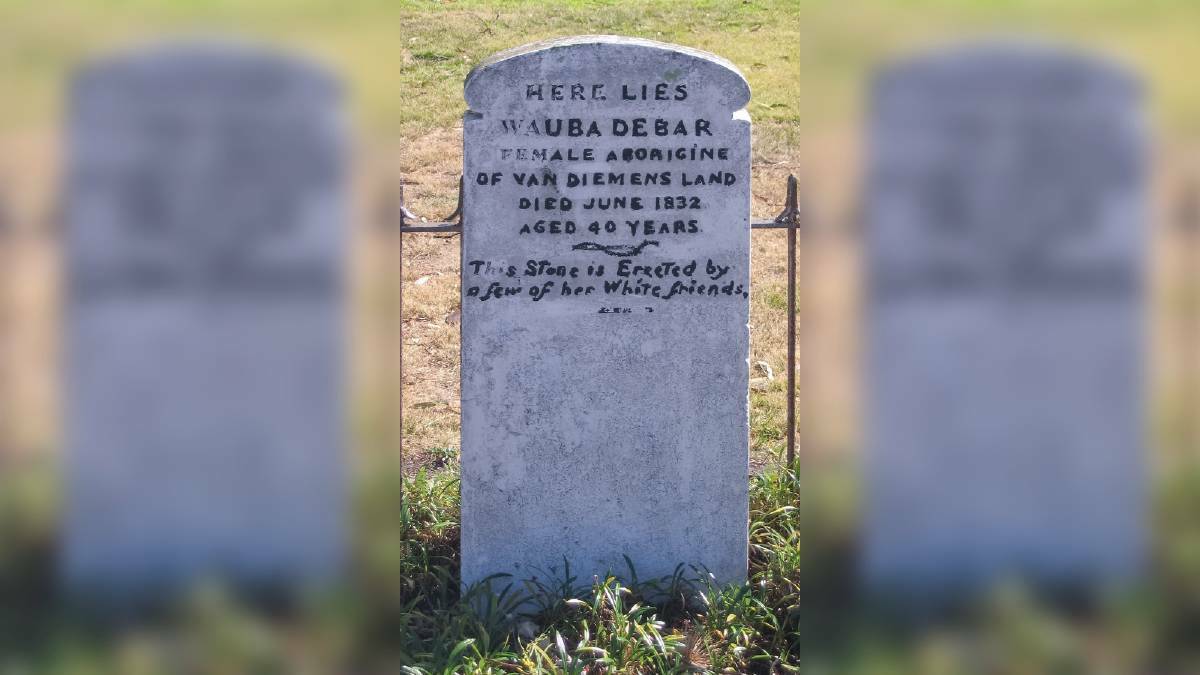

Instead of being celebrated as a hero, she ended up dying aged just 40. And instead of gold medals, it is a cold piece of stone inscribed with her name marking her burial place.

READ MORE: Meet Tasmania's very own Sheldon Cooper

The name Wauba Debar is not foreign to many who know Tasmanian history, but the entire truth of her life is one that is not known in any circle and one that continues to confound historians.

Though her name might not grace the competition name at the Launceston Aquatic Centre, her swimming heroics had a life-changing impact on at least two people.

It is said that such was her swimming proficiency, she was able to save the lives of two men who were all at sea and struggling to keep their heads above water after their sealing ship hit trouble.

In came Debar, bringing both men to safety and returning them to a Bicheno beach.

At least, that is how the legend goes.

University of Tasmania Pro Vice Chancellor of Aboriginal Leadership and Aboriginal history researcher Professor Greg Lehman cast doubts over the likelihood of the Tasmanian legend.

He detailed how certain elements of the story did not quite add up, and how several historians over the journey had only ever really scratched the surface of who Wauba Debar was, and what exactly her exploits were.

There are no known contemporaneous reports of the famed swimmer, and the earliest known account of anything linking to her is the grave of "Campbell's black woman" at Stoney Boat Harbour, which is not the Gulch at Waubs Bay.

Even the name of the bay, Waubs, has presented confusion.

At first take, the obvious answer is the bay was named for the legend. An early diary entry from Captain James Kelly detailed a landing at Waubs Boat Harbour in January 1816 might be a red herring. Confusion persists as to whether the harbour was in fact named before the death of Wauba Debar.

A report from the explorer Henry Rice says some form of gravestone existed at the spot 12 years earlier, but that it was at Stony Boat Harbour.

The timeline is confounding, and perhaps the reason the story has continued to leave historians puzzled.

One fact has a clue as to Wauba Debar's story, and it came in an unlikely way.

The payment for the headstone to be placed at the gravesite has been traced to John Allen, a man who owned 400 acres of land at Swanport. But that gravestone was not paid for and erected until 1855 when Allen was 52.

Well-researched historical references to Allen show his farm was regularly set upon by Aboriginal people, and after one such attack he sought retribution.

During the final attack, in February 1828, the farm's first wheat harvest was said to have been burnt, and his house destroyed by fire. The damage was estimated to have been 300 pounds. A princely sum at the time.

For his loss, heritage records indicate Allen applied to the Colonial Secretary for reparations in the way of a 200 acre extension to his farm. The Colonial Secretary happily approved the request, much to the delight of Allen.

On December 14, 1928 the farm was attacked again and apparently left Allen devastated. In the immediate aftermath of the attacks, Allen or one of his offsiders reportedly found the time to sketch a picture from memory of what had transpired.

The sketch was later turned into an oil painting, which is now at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery.

The painting is some way removed from the sketches, and art historian and art theorist David Hansen from the Australian National University thinks, like Wauba Debar's story, the oil portrays a "mythic encounter" where "vision enters the service of ideology".

As researched by Hansen, the sketch started as depicting the "attacks" by a group of 13 Aboriginal people, the number grew to 18 as part of an inscription.

And this number became more mythical still when Allen's own headstone was inscribed as saying he had "fought a tribe of Aborigines singlehanded on the 14th December 1828".

Five days later, Allen applied to be a Special Constable of Great Swan Port. Of which he received approval and a nominal wage.

Months later, in June 1829, Allen applied to be appointed District Constable, which the Colonial Secretary again approved.

The secretary wrote Allen was happy to be appointed to the role as "a small help will be acceptable after the many losses [Allen has] sustained from the Black Natives".

The title came with the land and a nominal wage.

While the link between Allen and Wauba Debar is obvious in his paying for her headstone, the more tenuous link is why?

Dr Lehman believed the act of paying for the gravestone was his means of making amends.

The possible need to make amends was passed down the line of the Allens.

A relative of Allen, Edith Allen, paid to have a fence put around the Bicheno site in 1926, 47 years after John Allen had died.

In what appears to be the same Edith Allen's will, she dedicates money to the upkeep of her family's graves.

"I devise and bequeath ... to retain the sum of fifty pounds to apply the same together with any interest accruing thereon from time to time in their absolute discretion for the upkeep of the graves of my mother and father and brother at Bicheno," it reads.

There is no allusion to the idea Edith Allen may be a descendent of Wabau Debar, but the fact remained the upkeep of graves appears to have run in the family. In her lifetime Edith Allen took it upon herself to maintain the legendary grave of Wabau Debar, and even prevent it from ransacking by erecting the fence, and after her death she did the same from her mother, father and brother.

- The third part of this story will feature in the next Sunday Examiner

What do you think? Send us a letter to the editor: