Waverley woman Deb Ballenden comes to a pause as she explains to me how she skips lunch and her diet is mostly just eggs so she can save a little bit of money each week in case of emergencies.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

or signup to continue reading

She had come to the Ravenswood Neighbourhood House to collect a bag of vegetables from the Loaves and Fishes program before they ran out, because her pension only stretches so far and it's difficult to find fresh food locally.

But the more she spoke about how her neighbour - also on the aged pension - and herself had very little left over week-on-week, the more she became frustrated.

"I just think, in the government, you need to have just a normal person that has been through all the hardship, that knows what it's all about. They should be in government, instead of these people who don't know how it is," Deb says.

It's not an uncommon sentiment to hear from those struggling on government pay, whether it be JobSeeker, Carers, the aged pension or student payments.

The overwhelming view is that governments don't listen, or just don't really care about how those on welfare payments live.

And the more disengaged and disillusioned they become with politics and politicians, the easier it is for governments to just ignore their struggles. That partly explains why the base rate of JobSeeker - formerly Newstart - hadn't risen in real terms since 1994, and when it did finally increase, it was by just under $4 a day.

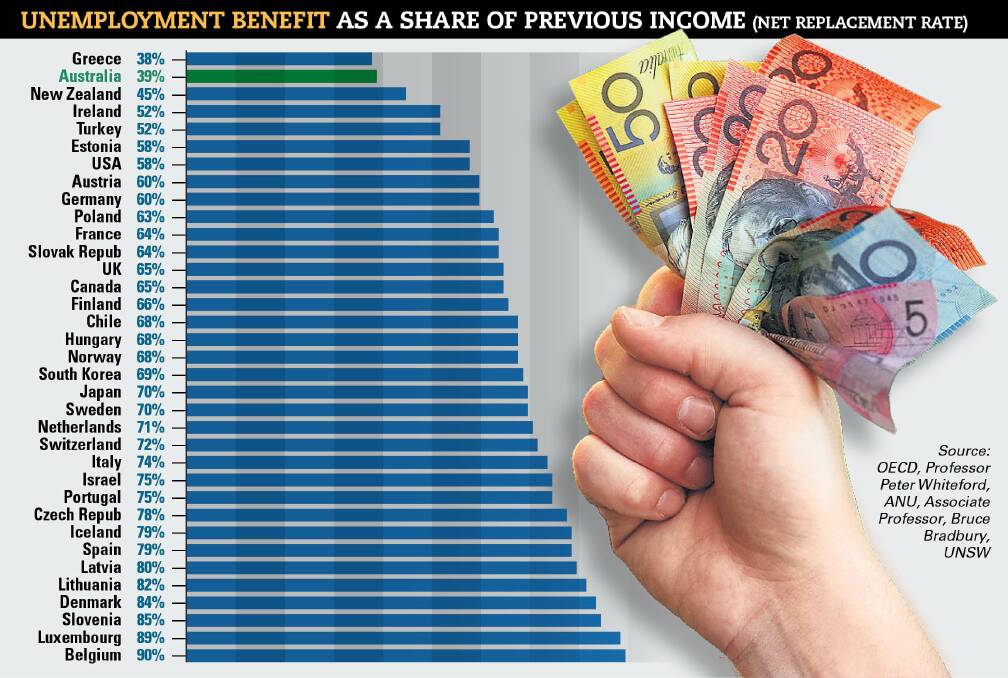

The government trumpeted this as a generous increase, taking it to 41 per cent of the national minimum wage. Using that same metric, Australia went from having the lowest unemployment benefit in the OECD, to the second lowest, moving ahead of Greece. It's a substantial leap to the next lowest - New Zealand and Ireland - whereas the unemployment benefits in the Netherlands, Italy, Spain, Denmark and Belgium are all above 70 per cent of their minimum wage, some of which are systems where workers and employers contribute to unemployment insurance, among other policies.

The government's lack of understanding of the struggles of people living on our comparatively small amount of welfare is also why they feel they can pursue paternalistic policies targeting the poor or marginalised. See the Northern Territory Intervention, Work for the Dole, mutual obligations and Robo-debt, for starters.

In each of those cases the government either made no attempt to understand the impact of these policies, or when they did have data, they just ignored it.

There's a new example to add to this growing list: the cashless debit card.

Earlier this month, the government finally released the long-awaited report into the Indue card - a report it commissioned itself, from Adelaide University, for $2.5 million.

It's just a shame that the report was made publicly available almost two months after the matter had been voted on in Parliament, in which it was extended in existing trial sites by another two years.

The report involved two years of extensive interviews with CDC participants in the trial sites: Ceduna, East Kimberley and the Western Australian Goldfields. It was the most comprehensive analysis of the effectiveness of the scheme thus far, including responses from businesses and service providers. Holding it back so late only raises suspicion that it was likely to be damning. But was it?

The first thing to note was that the outcomes weren't all bad. Alcohol and illicit drug use decreased, gambling experienced a "modest reduction", and Aboriginal participants reported a slightly improved level of control over their lives and money. The report also noted, however, that other interacting policies could have impacted consumption.

When it came to financial planning, money management, child welfare and employment outcomes, there was little change. The government has promoted the card as reducing family violence, but the report found that was not the case, and in the East Kimberley it may have increased.

Participants regularly reported the inability to provide cash to their children and grandchildren, being unable to buy cheaper items from online sellers, increasing instances of financial abuse of older people and experiencing a negative effect on their psychological wellbeing.

The "blanket approach" was considered inappropriate by many, with respondents working part-time, participating in Work for the Dole, managing their money well and with no substance abuse issues seeing it as an unfair punishment.

"I'm a 55 year old widow. I don't do drugs. I don't drink alcohol. I don't gamble. What am I doing sitting on the Indue card?" one respondent said in the report.

Another responds that, because the regions are so remote, most of the service stations and rural stores are licensed premises meaning they can't buy anything with the Indue card - including food, accommodation or fuel.

Even when the answers are right there in black and white, the government ignores them. Were it not for amendments in the Senate at the last minute, the program would have been expanded further.

How can we expect people to have faith in politics, in governments, when policies only seem to go in one direction: to punish, not to work with those affected to find solutions.