Light filters through a canopy of eucalyptus regnans and peppermint gums. Looking up from their wide, moss-covered bases, it's difficult to see the tops of these tall trees.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

or signup to continue reading

They're set near several tall blackwoods that have stood for at least a century.

Alongside them are musk trees, their short stature belies their age. The slow-growing trees are, from any objective assessment, well over 100 years old.

Sassafras grow at irregular angles in a rainforest understorey which starts to open up the further you descend into the forest.

And then the tree fern glades emerge, most at least five metres in height. Adding between two and three centimetres per year, they are estimated to have grown for at least 200 years.

Apart from the occasional sassafras, the tree ferns grow in wide areas with few other trees.

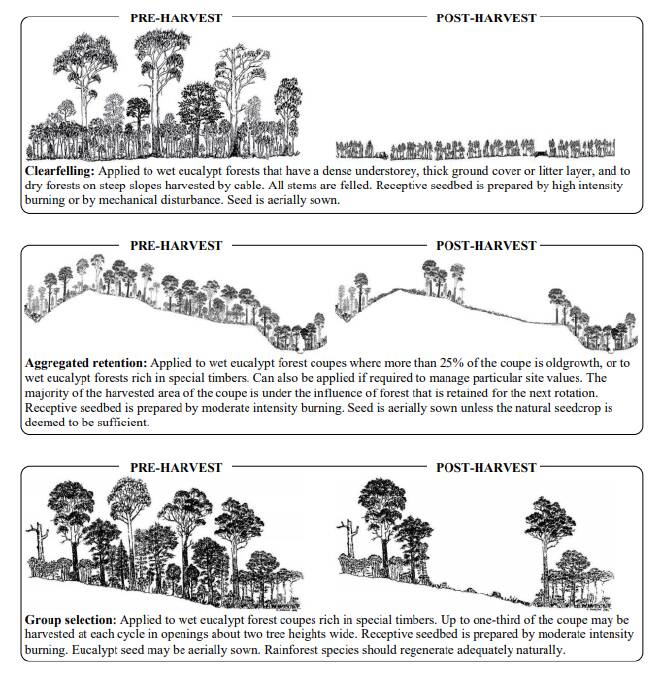

At some stage this year, machinery will roll in and the entire forest will be removed by the state's public forestry enterprise, Forestry Tasmania, which has traded as Sustainable Timber Tasmania since 2016. What remains after clearfelling will be burnt away, leaving the landscape as an ash-covered rolling hill, albeit temporarily.

This 50-hectare section of native forest is known as CC161B in the Mutual Valley near Derby, which environmental groups consider is a connectivity corridor to the Blue Tier. "Old growth" has become a political term, but the vast majority of this area is untouched.

"Even if it was one guy in 1853 coming through with a bullock team and choosing just the best logs, that stops it being called 'old growth'," forest campaigner Louise Morris said. "What they're doing now - clearfelling - hasn't been done to these forests before."

It will join a patchwork of neighbouring forestry coupes - some harvested recently by STT, others transferred from the failed Gunns to become plantation in recent decades. The valley provides a working example of changes in Tasmania's forestry practices over the years. From the clearing of native forest for plantation in the past, to current practices of regenerating native forest after harvesting using aggregated retention, seed trees or simply clearfelling and resowing the entire coupe, the area shows whether attempts to regenerate the native forest landscape are actually working.

Because while CC161B will sit as a relatively barren expanse initially, not long after it will be reseeded with a native species - most likely eucalyptus obliqua. As the years pass, the replacement trees will sprout from the ground at an equal age, creating a more uniform native forest than existed previously to be logged again later this century.

Can clearfelled 'old growth' ever really be regenerated?

Driving through the Mutual Valley, on the left sits a section of native forest with an understorey typical of a rainforest, untouched with tree ferns and tall eucalyptus regnans. On the right is an impenetrable patch of vegetation. This was clearfelled in the past and reseeded with eucalyptus obliqua, but invasive weeds have infiltrated the boundaries.

The difference is quite stark.

"So they've changed from what we have on the left - which is super wet and a natural fire break in the landscape - to what we have on the right, which is a mass of even-age, flammable vegetation," experienced Tasmanian reserve manager Mike Bretz said. "They've converted what was eucalyptus regnans - the tallest flowering plant in the world with a rainforest understorey - which they've logged, and reseeded with eucalyptus obliqua which is much drier."

The issue of the flammability of regrowth forest has been a source of contention, particularly after a University of Tasmania paper that found logging made forests more flammable was retracted. This was due to the reliance on Tasmanian government data that had been incorrectly categorised.

Researchers, contacted by The Examiner, agree there is a shortage of Tasmania-specific studies in this area. The role of the Simsons stag beetle which lives in the Mutual Valley, among other species, is still little understood when it confronts clearfelling.

STT says it chooses eucalyptus seed "from the harvested area or the surrounding forest", aerially dropped on the site.

"Only eucalypt seed is sown and understorey species regenerate from either ground stored seed, coppicing or recruitment from surrounding forests. Eucalypts create conditions for other species to grow as part of the understorey," an STT spokesperson said.

So what does this look like in practice?

One observed area is left with a "seed tree" to aid in regeneration, although on closer inspection, it appears to have died. Environmental groups say this is due to the practice of burning the land post-harvest, which they claim gives the remaining tree little hope of survival.

STT claims that burning post-harvest is needed to "achieve a similar result to what nature achieves through bushfires" by removing dense understorey and litter that "prevents the continuous regeneration of eucalypts".

They provided a 2010 technical bulletin that described the need to create a "receptive seed bed" with various types of mineral soil through burning. The process of "clearfell, burn and sow" was established in Tasmania in the 1950s and '60s, with attempts to refine in the next decades for various forest types.

In 2005, "aggregated retention" became a preferred method - retaining small patches of native forest among the clearfelling to "provide for all old growth biota" where appropriate.

Aggregated retention efforts can be seen in the Mutual Valley. In one, a large retained tree has fallen over. The trees and understorey huddle together surrounded by bare earth where there once stood continuous forest.

University of Tasmania researcher Nick Fitzgerald has studied the state's native forests, soil composition and ecological changes for several decades. He doubts the effectiveness of aggregated retention in helping to restore old growth native forest to its former state.

"It's attempting to replicate that natural mixed-age forest so there are still some habitat trees. It's problematic though, because it's not unusual to see those little islands of retained trees being scorched during the regeneration burn," he said. "You've got a little patch of trees with an understorey that used to be continuous forest suddenly exposed on all sides to sun and wind. It dries out, and it gets wind damage."

He agrees that the "ash-bed effect" after burning does aid in growing eucalypts, but other species - like myrtles - will struggle in the North-East where they have relied on a rainforest understorey that can't be regenerated so easily.

"While it is true that bushfires promote eucalypt regeneration, they typically result in multi-aged forests with large trees surviving the fire along with the young regrowth, unlike clearfelling. What happens if a wet eucalypt forest is not burnt or logged? The answer is: it transitions to rainforest," he said.

CC161B won't have aggregated retention, either. It's described as "clearfelling", meaning everything will go, to be replaced with eucalytus obliqua.

Why harvest native forest, anyway?

On a fact sheet, STT describes native forest harvesting as providing eucalypt and veneer logs for "appearance-grade timber" and structural timber.

Blackwood, celery-top pine and sassafras provide specialty timber, while "lower quality logs" are described as an "unavoidable by-product" of its operations. Pulp logs are woodchipped or exported whole for paper.

Back in CC161B, will those musk trees or misshapen sassafras be used for their natural qualities, or pulped? A Forest Practices Plan has yet to be released for the coupe, so it's difficult to say for sure. But the tree ferns are typically seen as "salvage", exported to local and European markets.

STT did not respond to questions about tree ferns as salvage.

In 2019/20, STT supplied 119,000-cubic-metres of native forest sawlogs. In 2016, STT highlighted its minimum legislated supply of high-quality sawlogs was 137,000-cubic-metres, a figure it estimated it would fail to reach.

Tasmania has an extensive plantation timber industry, a legacy of past practices of converting native forest to plantation. This conversion doesn't happen anymore, but like with Hydro, it's already in place and providing benefits for the state.

The Tasmanian Greens have proposed accelerating the transition to "high quality plantation timber" by establishing more locally-based processing options.

Tasmanian Forest Products Association chief executive officer Nick Steel said there were certainly opportunities to further develop "downstream processing" locally.

But he stopped short of agreeing with the Greens that such developments could replace the need for native forest harvesting.

"Our native timber can't be replaced by plantations. It's complementary, we need to have both within the state," Mr Steel said.

"Specialty timbers is something that's iconic to Tasmania. Sassafras and myrtles, this is what Tasmania is renowned for. That's something that plantations can never take over."

When it came to environmental concerns, Mr Steel said the state's regulator - the Forest Practices Authority - had to sign off on plans to log coupes. He had faith in the regulatory process.

"They consider the best silvicultural evidence for each forest. There are exclusion zones for different types of flora and fauna, wedge-tailed eagles and others, streamside reserves and measures to stop erosion," he said.

STT has yet to achieve Forest Stewardship Council certification, however, limiting its access to a range of international markets. In the latest audit, the harvesting of potential nesting and foraging trees in sight of swift parrot nesting sites, insufficient hollow-bearing tree retention and lack of transparency were criticised.

When asked about hollow-bearing trees in CC161B - which is scheduled for cleafelling - STT stated it identifies measures to protect "special values" such as "important habitat features".

Economist John Lawrence has written extensively about the financial opaqueness of various Tasmanian industries, from the pokies to native forestry. In 2018, he again sounded the alarm about STT's finances, describing a $454 million loss between 1997 and 2017.

He said STT's dependence on government subsidies had started to reduce - from $22.8 million to $15.4 million between 2018/19 and 2019/20. But he still believed it was an unsustainable enterprise, including concerns that native forest was being felled prematurely due to log size limitations at TaAnn's mill. He said the prices for these logs was "not much better than woodchip prices".

RETURN OF THE FOREST WARS?:

- Two charged at Bell Bay timber bill protest, log trucks bank up, tempers flare

- What Bob Brown's Federal Court challenge to forestry in Tasmania came down to

- Return of the forest wars? Land available for logging as moratorium ends in 2020

- STT audit details swift parrot habitat loss and old growth harvesting

- Bob Brown arrested in Eastern Tiers for second day in a row during protests

Mr Lawrence also claimed STT was overstating its future net income by not including road access or replanting costs.

"The calculation of profits as per the financial statement excludes the costs of building road access to coupes and replanting costs. These are considered to be capital expenses. Were these to be included then logging most coupes would be unprofitable," Mr Lawrence said.

In its latest annual report, STT boasts that its operating cash flows were strong compared to the previous year with a $3.9 million underlying net profit.

Can native forestry coexist with Derby's tourism?

Heading into the Mutual Valley, a sign at the end of a driveway invites tourists into a forest cabin accommodation business.

From the cabins, coupe CC161B sits within clear view on the adjacent hill. It painted a picture of the reality of native forestry and tourism working in the same landscape. The industries have a memorandum of understanding, but does that work on the ground?

Jules Seymour runs a property management business for short-term accommodation properties around the area. She moved to Derby four years ago, one of the many who have been drawn to the town recently as it became Tasmania's premier mountain biking destination.

Ms Seymour said a lot of her clients were worried about how native forest harvesting would impact tourism, but were afraid of commenting publicly.

She understands why there's such passion. Native forest harvesting provides a livelihood for some locals. The TFPA estimates that 5700 people are employed either directly or indirectly in forestry statewide, although the breakdown of native versus plantation jobs wasn't provided - many contractors work in both.

"At the end of the day, the truckies have a family to feed, it's not their fault. They would feel attacked if people want their industry shut down, but there has just got to be a better way," Ms Seymour said.

"There's a long history in Tasmania around this, I know how much it affects people when businesses close. But for our next generations, how is it sustainable to keep logging old growth forests?"

Nowhere is the cross-over between native forestry and tourism greater than near the top of Krushkas trail, one of Derby's most popular and challenging mountain bike experiences.

Further along from the landmark Big Mama tree, native forest has been cleared for access roads and a log landing for coupe CC105A, with a boundary of between 20 and 50 metres from the trail. This is in the Permanent Timber Production Zone, after all, an area designated for potential logging before the trails came into existence.

Walking along Krushkas, a section of the trail near the recently-established log landing has far more fallen branches and toppled shorter trees than other areas.

Mr Bretz said this is a symptom of "edge effect", when the forest closest to clearing is exposed to more wind and solar radiation. He said the logging might be dozens of metres away now, but over time the forest could degrade closer to the trail.

While walking up Krushkas, a group of mountain bikers stop to chat with Mr Bretz and Ms Morris about the STT posters they've seen around Derby with the heading "What's Happening at Krushka's?".

One of the group, from Sydney, said he would encourage others in the mountain biking community to lobby to stop native forestry in the Mutual Valley. They feared it would end up like Rotorua in New Zealand, where he said forestry had "ruined" the mountain biking experience.

'Wood is good'

STT has no greater backer than Resources Minister Guy Barnett, closely followed by Labor's primary industries spokesperson Shane Broad. Dorset Council mayor Greg Howard also vigorously defends the industry from its detractors.

Native forestry has bipartisan support with Labor wary of being lumped in with the Greens should it raise any issues with STT's operations.

One of the biggest changes to forestry policy occurred last year when a moratorium on logging in 356,000 hectares of native forest came to end, allowing companies to apply to log the Future Potential Production Forest areas. The government was hardly flooded with interest, however.

In 2019/20, STT harvested almost 5800 hectares of native forest, slightly less than the 12 months prior.

Mr Barnett continuously goes into bat for the industry with his usual slogan of "wood is good", or that the industry was providing "the ultimate renewable".

He believed harvesting practices were adequately regulated.

"Let's be very clear: the industry must abide by those rules. They cannot breach those rules," Mr Barnett said.

He wasn't concerned about native forestry potentially impacting Derby's tourism potential.

"That's one of the reasons that Derby is so successful. It's in an area that is forested, and it's been provided there with the support of STT and the forest industry," Mr Barnett said. "You can have tourism, you can have forestry, you can have productive industries working successfully with our tourism industries."

One of those who knows all too well the local blowback in raising native forestry concerns is Blue Derby Wild co-ordinator Louise Morris. Along with Mr Bretz, they carry out constant monitoring of local forests - and they say the issue won't be going away.

"I think people thought that, post-Tasmanian Forest Agreement, this had been solved because there was so much media of, 'oh, the forests are saved'," Ms Morris said. "But no one actually looked behind the buffer so to speak, that some areas might have been saved, but really, it's just business as usual."

A STT spokesperson said Forest Practices Plans for CC161B and the two Krushkas coupes were still being developed.

"Detailed operational planning is carefully undertaken in the preparation of Forest Practices Plans to identify special values within any potential harvest area, and identify specific measures to appropriately protect these values such as important habitat features and the location of harvest boundaries," the spokesperson said.

"The coupe context is also incorporated into the detailed operational planning and scheduling. This can include longer-term use of roads to enhance access for mountain bike trails, apiary sites, forest management and fire protection."