WARNING: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are warned that the following article contains images and names of deceased persons.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

or signup to continue reading

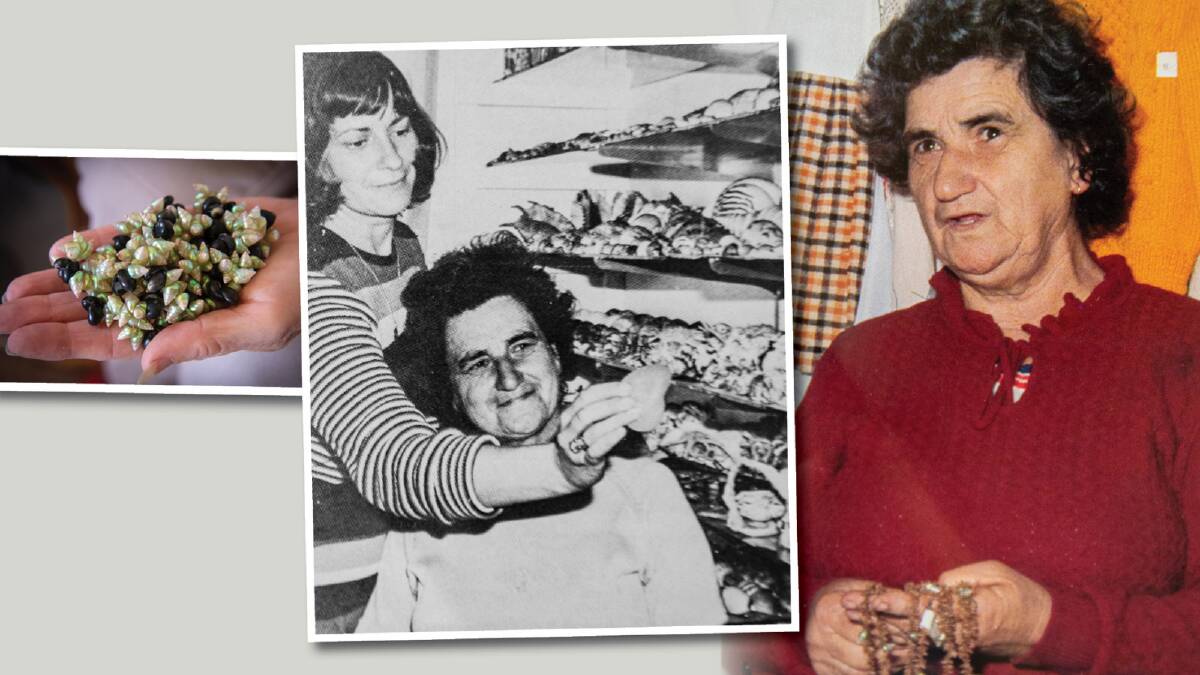

The life of the oldest surviving Aboriginal person in Tasmania ended on December 14, and with her life went centuries of knowledge.

But such was Aunty Dulcie Greeno's commitment to passing on that knowledge, she has been credited with reviving, sustaining and furthering culture of the Tasmanian Aboriginal people for generations to come.

Aunty Dulcie, aged 98 when she died, was born on Cape Barren Island in 1923.

The future of a possible treaty in Tasmania was further away than the forced removal of Aboriginal people from the mainland of the island state was in the past.

And part of the role Aunty Dulcie played in reviving ancient palawa traditions can objectively be defined as being part of the reason a treaty in Tasmania is talked about today.

She was the last surviving of three custodians of the Aboriginal necklace makers or stringers - a palawa tradition credited as being one of the culture's oldest legacies.

That tradition involves collecting barely larger than rice-sized shells, washing and drying them, and stringing them by hand. They range in length and can be metres long.

Auntie Dulcie has been credited as having recovered that tradition, alongside two others, and making it one of the most openly revered cultures in Tasmania today.

Her daughters, Aunty Betty Grace and Dr Aunty Patsy Cameron reminisced about the significance of their mother to not only their own family, but the entire Aboriginal community.

She was defined by necklace making. From when she was a little girl she loved collecting shells, it was in her blood.

- Aunty Betty Grace

"When she was collecting shells she was head down and bottom-up, and we just followed what she was doing. She was very committed that the tradition should be passed on and she made sure we girls did it right," Dr Aunty Patsy said.

While stringing and making necklaces was no doubt an enjoyable pastime for Aunty Dulcie, it was clearly more than that to her. Her daughters explained she was very much aware of why she needed to carry the culture of necklace making on her shoulders.

Aunty Dulcie bore that load with two other elders, Aunty Joan Brown and Aunty Muriel Maynard, and the three of them were known as the three great shell stringers, and the custodians of the practice. They were transparently tasked with sharing their necklace making knowledge with the next generation of necklace makers.

With the death of Aunty Dulcie, all three great shell stringers have gone, and the responsibility for retaining the shell stringing knowledge now rests firmly with the next generation.

Dr Aunty Patsy estimated that knowledge had been embedded in about 40 contemporary stringers living across Tasmania today.

But when Aunty Dulcie first learned the craft, that number was small and dwindling. And it was only because of her connection to the land that she learnt it in the first place.

When she was a child her parents followed the seasons - from tin mining season, to mutton birding season, and others in between. As her family travelled from Babel Island, to Cape Barren Island, to Flinders Island, Aunty Dulcie learnt her craft, developed it, and honed it based on the different shells she could find on each island.

And it was through he connection with the land synonymous with Tasmanian Aboriginal people, and a genetic affinity for collecting shells, that she found her place in history.

Greg Lehman, a descendant from the Trawulwuy people and the Pro Vice Chancellor for Aboriginal Leadership at The University of Tasmania, knew Auntie Dulcie well.

He grew to know when she became actively involved in research projects with the university aimed at supporting the continuation of shell necklace making, and understanding its sustained importance.

"Aunty Dulcie was able to step into the university environment with her cultural knowledge and be recognised as an authority and a senior knowledge holder," Mr Lehman said.

She was able to help the academic world recognise Aboriginal knowledge is up there alongside the greatest knowledges in the entire world.

- Pro Vice Chancellor Greg Lehman

"She was recognised with the same sort of status that a professor might have in the academic world. She was recognised as a senior educator, and of the same caliber as anyone at the university.

"She was able to do that because the knowledge she held, and recognised the importance of sharing, was as any set of knowledge in the western world.

"Her legacy - the power and greatness of this woman - can be seen in her legacy continuing on in her family."

Dr Aunty Pasty said Auntie Dulcie's death brought great sadness, but was able to find solace in the fact the memory and knowledge of mother would never die.